Introduction to Neuro-Symbolic Modeling

PUBLISHED October 01, 2025

Does Successful Prediction Imply Understanding?

Today’s AI systems are quite sophisticated. But do they actually “comprehend” the phenomena they model? Or, do they merely exploit statistical patterns in data? Is there even a difference?

To better appreciate this distinction, let us go back in time to 585 BCE. The ancient Greek historian Herodotus tells us that Thales of Miletus successfully predicted a solar eclipse that occurred on May 27th of that year. This was a remarkable achievement for its time and has been celebrated as one of the earliest recorded instances of astronomical predictions in the Western world.1

Did Thales understand how eclipses worked? Thales, likely learning from Babylonian astronomers, had discovered cyclical patterns in celestial observations. The Babylonians had engaged in what we might today call “data mining”: systematically analyzing historical records of lunar and solar eclipses to identify recurring cycles. Luck may have also factored into Thales’ prediction.

Yet, neither Thales nor the Babylonians understood the actual mechanism behind eclipses.

The recognition that solar eclipses are caused by the Moon coming between the

(Westfall & Sheehan, 2015)

Earth and the Sun did not actually come until over a century [after Thales].

Thus Thales cannot have predicted an eclipse in any modern sense.

The story reveals a fundamental difference between prediction and understanding. The ability to find patterns in data and make accurate predictions does not necessarily indicate genuine understanding of the underlying phenomena.

By itself, this shouldn’t be a problem. However, as we will see, predictions based solely on pattern recognition without theoretical grounding are vulnerable to pathological failures when conditions change or when spurious correlations disappear.

Our Best Pattern Recognition Machines

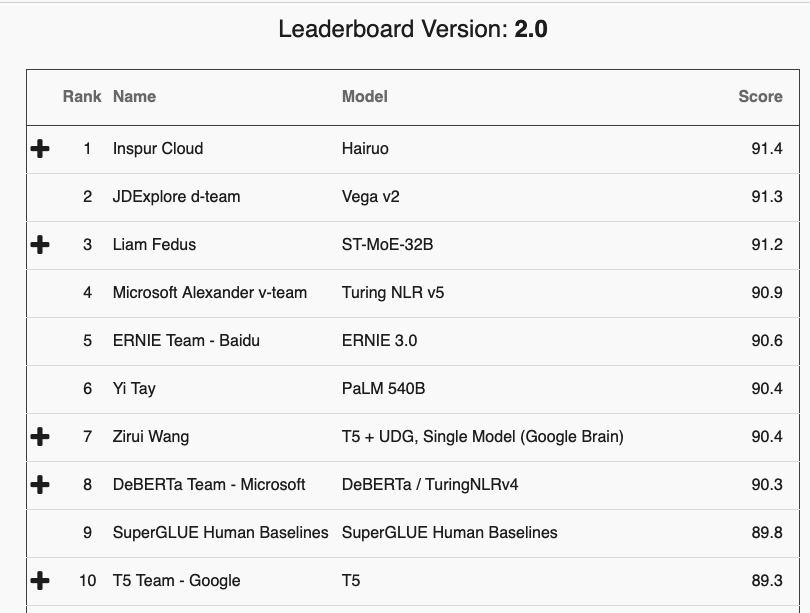

The SuperGLUE leaderboard on Nov 13, 2025

Neural networks are the dominant drivers of contemporary artificial intelligence. Their successes are remarkable and span computer vision, natural language processing, speech recognition, and many other domains.2 The scale and sophistication of these systems continue to grow, with large language models now trained on trillions of tokens and achieving superhuman performance on various benchmarks.3

The SuperGLUE benchmark suite for text understanding (Wang et al., 2019) provides an illustrative example. As of this writing, eight of the top ten models outperform human baselines; an achievement that suggests a significant milestone in AI development, and implies that machines have been able to surpass human performance in certain aspects of language comprehension.

There are many other successes with near-human performance on increasingly difficult benchmarks. OpenAI’s GPT-4 (OpenAI, 2023) reported 95.3% accuracy on the HellaSwag dataset (Zellers et al., 2019), which evaluates commonsense reasoning abilities. This score came within 0.3% of average human performance and exceeded the second ranked system by about 10%. Google’s Med-PaLM 2 (Singhal et al., 2023) not only achieved a passing score on US Medical Licensing Examination-style questions but also impressed medical specialists: for nearly two-thirds of real-world medical questions, they preferred its answers over those provided by generalist physicians.

However, these successes come with caveats.

Data Hunger

Modern neural networks, especially large language models, require massive amounts of data to achieve their impressive performance.

Consider how text datasets for training large language models have grown. In 2020, the largest datasets were the Colossal Cleaned Common Crawl, or C4, (Raffel et al., 2020) and the Pile (Gao et al., 2020), with 175 billion and 387 billion tokens respectively.4 In mid-2024, the largest public dataset was Dolma (Soldaini et al., 2024) with three trillion tokens. By year’s end, FineWeb (Penedo et al., 2024) had surpassed it with 15 trillion tokens. These are merely the public datasets. Proprietary language models may be trained on even larger corpora.

Why do these datasets keep growing? The short answer is that models trained on larger datasets perform better on benchmarks. However, this dependency on massive pre-training corpora raises questions about the scalability and sustainability of current approaches, particularly for domains, languages or tasks where large datasets are not readily available.

Massive Inscrutable Models

Dataset growth has been matched by parameter expansion. Language models of 2018, like BERT (Devlin et al., 2019) and the original GPT (Radford et al., 2018), had hundreds of millions of parameters. By 2024, the largest publicly disclosed language models had hundreds of billions; for example, DeepSeek-V3 (DeepSeek-AI et al., 2024) had 671 billion parameters. As with dataset sizes, we can only speculate about proprietary model sizes.

Remark: The sizes of pre-training datasets and language models interact with training compute requirements in interesting ways. The so-called scaling laws for language models (Kaplan et al., 2020) study this relationship empirically, and guide how language models are trained.

Why are the immense sizes of language models a limitation? First, larger models demand more expensive compute resources for both training and deployment. Second, understanding their decision-making processes becomes challenging. The internal representations learned by these systems are often opaque, making it difficult to audit their reasoning processes or identify potential biases and failure modes.

Reasoning Failures

Despite benchmark successes, neural networks often fail in ways that suggest a lack of genuine understanding. These failures become apparent when we examine their performance on tasks requiring logical consistency, systematic reasoning, or explicit rule application. Let us look at some examples next.

Failures in Reasoning and Understanding

The answer becomes clearer when we examine these systems more carefully through the lens of structural knowledge and reasoning principles. Despite their impressive benchmark performance, modern neural networks exhibit systematic failures that reveal fundamental gaps in understanding—failures that would be inconceivable for systems with genuine comprehension.

Visual Reasoning

Consider a visual question answering system, trained on hundreds of thousands of image-question pairs, asked to answer questions about images. When presented with a photograph of a desk workspace and asked “Where is the penguin?”, a state-of-the-art VQA model from 2018 (Jiang et al., 2018) confidently responds with location predictions: “on desk” (37% confidence), “desk” (15% confidence), “on table” (12% confidence). The model’s attention mechanism even highlights regions of the image corresponding to these predictions.

[Figure 3: VQA example showing desk workspace with question “Where is the penguin?” and model predictions]

But here is the fundamental problem: there is no penguin in the image. When subsequently asked “Is there a penguin in the image?”, the same system responds with near-certainty: “no” (100% confidence), “yes” (0% confidence). The model simultaneously holds contradictory beliefs—asserting both that a penguin exists at a specific location and that no penguin exists in the image. These responses cannot both be correct, yet the system lacks any internal consistency mechanism to detect this contradiction.

This failure reveals more than a simple error. It exposes the absence of any coherent theory of visual scenes that would enforce basic logical constraints. A system with genuine understanding would recognize that claiming “the penguin is on the desk” logically entails that a penguin exists in the image. The violation of such elementary consistency requirements suggests that the model’s seemingly intelligent responses emerge from statistical pattern matching rather than structured reasoning about visual content.

Text-Based Visual Reasoning

Even more striking failures emerge when we consider visual reasoning about text. When modern vision-language models are shown the word “zoological” with one letter circled and asked to count circled letters, they produce inconsistent answers depending on how the question is phrased.5

[Figure 4: The word “zoological” with the letter ‘c’ circled]

Asked “How many ‘o’s are circled?”, a recent frontier model responds: “There is one ‘o’ circled in the image.” Asked instead “How many letters are circled?”, the same model claims: “There is one letter circled in the image.” Finally, asked “Is the letter ‘c’ circled?”, it confidently asserts: “Yes, the letter ‘c’ is circled in the image.”

Given the first claim, at most one of the latter two can be true. If exactly one letter is circled and that letter is ‘c’, then no ‘o’ can be circled. Yet the model is devoid of any theory that would enforce this basic logical consistency. Could the model be trained to use such invariant rules? This question—whether neural networks can learn to respect declaratively stated logical constraints—lies at the heart of neuro-symbolic modeling.

Natural Language Inference

Perhaps most revealing are failures in natural language inference, where models must determine whether a hypothesis follows from a premise. Consider the premise: “Before it moved to Chicago, aerospace manufacturer Boeing was the largest company in Seattle.” Does this entail the hypothesis: “Boeing is a Chicago-based aerospace manufacturer”?

[Figure 5: NLI example with premise and hypothesis about Boeing]

A strong natural language inference model assigns high probability (75.6%) that the premise entails the hypothesis—that the truth of the premise guarantees the truth of the hypothesis. This judgment is incorrect; the premise actually contradicts the hypothesis, as “before it moved to Chicago” indicates Boeing was previously elsewhere, not that it is currently Chicago-based.

These errors extend beyond individual examples. Consider three statements forming a logical chain:

- P: John is on a train to Berlin.

- H: John is traveling to Berlin.

- Z: John is having lunch in Berlin.

A well-trained NLI model might correctly recognize that P entails H (being on a train to Berlin implies traveling to Berlin) and that H contradicts Z (traveling to a location contradicts already being at that location for lunch). However, the same system can simultaneously assign high probability to the judgment that P and Z have no inferential relationship, or even that P entails Z.

[Figure 6: Diagram showing the logical chain P→H, H contradicts Z, with the implied relationship that P contradicts Z]

These three beliefs cannot be simultaneously held by a rational agent. If P entails H, and H contradicts Z, then by the transitivity of logical entailment, P must contradict Z. This represents a fundamental logical invariant—a rule that must hold in any coherent reasoning system. Yet research has shown that BERT-based models achieving approximately 90% accuracy on standard benchmark data violate such transitivity constraints on 46% of a large collection of sentence triples.6

The pattern across these examples is consistent: neural networks can learn to mimic intelligent behavior on individual instances drawn from their training distribution, but they lack the structured representations and reasoning mechanisms that would ensure coherent behavior across related instances. They predict without understanding, much like Thales predicting eclipses without grasping celestial mechanics.

The Challenge of Modeling

These failures raise a fundamental question about our modeling strategies: Are we modeling problems in their full richness and complexity, or are we merely optimizing for performance on benchmark test sets?

The distinction matters profoundly. Benchmark performance measures whether a model produces correct outputs for a sample of inputs drawn from a particular distribution. It does not measure whether the model has internalized the principles, constraints, and causal relationships that actually govern the domain. A model can achieve high benchmark scores through clever pattern matching while remaining fundamentally misaligned with the structure of the problem it purports to solve.

This misalignment has consequences. Without grounding in underlying structure, models become brittle—performing well on inputs similar to their training data but failing unpredictably on inputs that differ in subtle ways. They cannot explain their decisions in terms of principled reasoning. They cannot be reliably controlled or corrected through high-level guidance. Most critically, they cannot leverage declaratively stated knowledge about the domain to improve their behavior or ensure consistency.

What we need are modeling strategies that depend on or expose an underlying theory of the phenomenon being modeled. Such strategies would reduce dependence on massive training data by incorporating structural knowledge that constrains the space of possible behaviors. They would enable forms of reasoning and planning that go beyond pattern recognition. They would provide mechanisms for human understanding and intervention through interpretable representations of knowledge and decision processes.

Without this theoretical grounding, we are, in effect, guessing equations in high-dimensional spaces without understanding what they mean—pursuing precise curve-fitting over genuine comprehension. This is the difference between Thales’ pattern-based predictions and modern astronomy’s mechanistic understanding of celestial motion.

A Brief History: Symbolic Artificial Intelligence

The current dominance of neural networks obscures an important historical fact: for much of AI’s history, a very different approach held sway. Symbolic artificial intelligence, sometimes called “Good Old-Fashioned AI” or GOFAI, pursued the explicit representation of knowledge through symbols, rules, and logical formulas, paired with well-understood algorithms for reasoning about these representations.

The Symbolic Tradition

The foundations of symbolic AI trace back to the 1950s and the Dartmouth Summer Research Project, often considered the birthplace of artificial intelligence as a field. Pioneers like John McCarthy advocated for systems that would represent knowledge in logical formalisms and reason about that knowledge through deductive inference. McCarthy’s “Advice Taker” program exemplified this vision: a system that could accept new information in logical form and reason about how to achieve goals given its knowledge.

Through the 1960s and 1970s, this approach generated influential systems such as ELIZA (Weizenbaum, 1966), a pattern-matching chatbot simulating a Rogerian psychotherapist, and PARRY (Colby, 1972), which simulated a paranoid schizophrenic patient. While these early systems relied on relatively shallow rule-based approaches, they demonstrated the potential for symbolic knowledge representation to enable targeted behaviors.

[Figure 7: Photo of John McCarthy]

The 1970s and 1980s saw the rise of logic programming languages like Prolog, which made logical inference directly executable. The central idea was elegant: represent what you know declaratively as logical facts and rules, then let a general-purpose inference engine determine how to answer questions or achieve goals.

Reasoning Programs

A particularly clear articulation of the symbolic vision appears in McCarthy and Hayes’ influential 1969 paper “Some Philosophical Problems from the Standpoint of Artificial Intelligence” (McCarthy & Hayes, 1969). They described “reasoning programs” that would:

- Accept various forms of input (images as arrays, utterances as sequences, sentences as parse trees)

- Represent all input situations and internal program states as symbolic expressions in a formal logic

- Encode data structures, agent goals and sub-goals, and behavioral rules within this logical framework

- Operate as a deduction engine that searches for strategies provably solving given problems

- Execute discovered strategies to accomplish tasks

This framework promised rich, auditable representations of knowledge and transparent decision processes grounded in logical inference. To understand both its appeal and its limitations, let us consider a concrete example.

An Illustrative Example: Planning a Trip

McCarthy’s 1959 work (McCarthy, 1959) presents a scenario that illustrates the symbolic approach: “Assume that I am seated at my desk at home and I wish to go to the airport. My car is at my home also. What should I do?”

[Figure 8: Illustration of the planning scenario with desk, home, car, and airport]

The symbolic AI solution begins by representing the facts of this situation in logical notation:

at(I, desk)

at(desk, home)

at(car, home)

want(at(I, airport))

Here, at(x, y) denotes that object x is located at location y, and want(p)

denotes that proposition p is a goal to be achieved.

However, solving this problem requires more than just facts. We need general

knowledge about spatial relationships and available actions. For instance, the

at predicate has transitive properties that must be explicitly encoded:

at(x, y) ∧ at(y, z) → at(x, z)

This rule states that if x is at y, and y is at z, then x is at z. Applied to our scenario, since I am at the desk and the desk is at home, we can infer that I am at home.

The system must also represent the conditions under which actions are feasible. Walking and driving have different preconditions:

walkable(x) ∧ at(y, x) ∧ at(z, x) ∧ at(I, y) → can(go(y, z, walking))

drivable(x) ∧ at(y, x) ∧ at(z, x) ∧ at(car, y) ∧ at(I, car) → can(go(y, z, driving))

These formulas specify when walking or driving from location y to location z is possible. Notice the complexity: we must represent not only that certain locations are walkable or drivable, but also that walking requires the agent and both locations to be in the same walkable space, while driving additionally requires the agent to be in the car.

To apply these rules, we need domain-specific facts:

walkable(home)

drivable(county)

at(home, county)

at(airport, county)

McCarthy’s paper continues with additional rules about the effects of actions, how goals compose, and strategies for planning. The complete formalization spans several pages—and this is for a toy problem involving a handful of locations and two types of actions.

The Brittleness of Hand-Crafted Knowledge

This example illuminates both the appeal and the fundamental limitation of symbolic AI. The appeal lies in the explicit, interpretable nature of the representation. Every fact, every rule, every inference step is transparent and auditable. If the system makes a mistake, we can trace through its logical reasoning to identify the faulty knowledge or inference.

The limitation lies in the sheer volume of knowledge that must be manually encoded. Consider what the example leaves implicit: How do we know that home is a walkable space? What rules determine whether two locations are in the same county? What about unusual situations—what if the car has a flat tire, or the roads are flooded, or it’s faster to walk because of traffic? The knowledge engineer must anticipate all such considerations and encode appropriate rules.

This manual knowledge engineering proved prohibitively expensive. Real-world domains involve thousands or millions of relevant concepts, intricate relationships between them, and numerous exceptions to general principles. Worse, the knowledge often proves brittle—systems work well only within the narrow scope for which rules were crafted, failing unpredictably on variations that require slightly different or additional knowledge.

Moreover, symbolic systems struggled with uncertainty and noise. Real perceptual data—images, speech, sensor readings—does not arrive in neat symbolic form. The problem of translating messy, ambiguous real-world observations into the crisp logical assertions required by symbolic reasoning systems remained largely unsolved.

Perhaps most fundamentally, hand-crafted rules failed to capture how complex phenomena like language and vision actually work in practice. Human language understanding does not proceed by explicit logical deduction over formal rules. Visual perception does not involve theorem-proving about spatial relationships. The symbolic approach imposed a structure on these domains that, while elegant in theory, proved mismatched to their actual character.

By the late 1980s and 1990s, symbolic AI’s limitations had become increasingly apparent. The field entered what is sometimes called an “AI winter”—a period of reduced funding and diminished expectations. The rise of statistical machine learning, and later deep learning, offered a fundamentally different paradigm.

Neural Networks versus Symbolic AI: Complementary Strengths

The contrast between modern neural networks and classical symbolic AI reveals less a clear winner than two approaches with profoundly complementary strengths and weaknesses. Understanding this complementarity motivates the neuro-symbolic synthesis.

Neural networks have emerged as the dominant approach for good reasons. They naturally work with probability distributions over possible outputs, gracefully handling ambiguous inputs and learning from noisy data in ways that symbolic systems struggle to match. Rather than requiring manually engineered features or knowledge, neural networks can learn directly from raw inputs—pixels, audio waveforms, token sequences—discovering relevant patterns through exposure to data. The ease of designing and training neural networks, relative to hand-crafting knowledge bases, has proven remarkably liberating. Standard architectures and training procedures apply across diverse domains, and the empirical results speak for themselves: neural networks achieve state-of-the-art performance on numerous benchmarks spanning vision, language, speech, and other modalities.

Yet these successes come with critical limitations. Neural networks do not naturally accommodate easily stated rules or constraints. If we know that certain outputs must satisfy particular logical properties, we cannot simply inform the network—we must hope it learns these constraints from data, often requiring vast numbers of examples to capture principles that could be stated in a single sentence. Despite their sophistication, neural networks do not truly perform reasoning in the sense of deliberate, step-by-step inference. They lack natural mechanisms for planning, systematic search over possibilities, or recursive algorithmic procedures. Perhaps most concerning for high-stakes applications, the decision processes of neural networks remain largely opaque. We can observe their inputs and outputs, but understanding why a network produced a particular output often requires sophisticated analysis techniques that provide only partial insight.

Symbolic AI offers a complementary profile of capabilities. Rules, constraints, and facts can be stated directly in logical form, expressing what must hold rather than laboriously encoding this knowledge through training examples. When systems need to perform logical inference, planning, systematic search, or recursive procedures, symbolic frameworks provide natural foundations. Every conclusion derives from explicit rules and facts through traceable inference steps, enabling full auditability of decision processes—a crucial property when explanations matter. Moreover, decades of research have produced sophisticated algorithms for logical inference, constraint satisfaction, planning, and related symbolic reasoning tasks, with well-understood computational properties and formal guarantees.

These advantages, however, come at a cost. Classical logic operates with crisp true/false judgments, struggling to represent and reason about uncertain, ambiguous, or noisy information—the very situations where neural networks excel. Symbolic systems require knowledge to be provided in symbolic form; they cannot directly learn from raw perceptual data or improve their behavior through exposure to examples in the way neural networks do naturally. Perhaps most limiting in practice, manually engineering comprehensive knowledge bases for real-world domains requires enormous expert effort and rarely achieves the completeness or robustness needed for reliable deployment.

The complementary nature of these strengths and weaknesses suggests a natural synthesis: combine neural networks’ ability to learn from raw data and handle uncertainty with symbolic AI’s capacity for structured reasoning and interpretable knowledge representation. This is the promise of neuro-symbolic modeling.

The vision is compelling. Imagine systems that:

- Learn rich representations from data through neural networks

- Respect declared constraints and logical principles through symbolic components

- Perform systematic reasoning and planning when needed

- Remain interpretable through explicit symbolic representations

- Leverage both learned patterns and engineered knowledge

Realizing this vision requires solving a fundamental technical challenge: neural networks operate with continuous vectors and differentiable functions, while symbolic systems operate with discrete symbols and logical operations. How can these paradigms interface with each other?

Neuro-Symbolic Interfaces: A Preview

Realizing the neuro-symbolic vision requires solving a fundamental technical challenge: neural networks operate with continuous vectors and differentiable functions, while symbolic systems operate with discrete symbols and logical operations. How can these paradigms interface with each other?

Multiple strategies have emerged, each representing a different point in the design space. At one end, we might simply use neural networks as components within symbolic pipelines—converting symbolic inputs to vectors, processing them neurally, and converting outputs back to symbols. This is what standard classification does, but it offers limited integration of symbolic reasoning into the learning process itself.

More ambitious approaches seek deeper integration. Some methods treat nodes within neural networks as “soft symbols” and compile logical constraints into differentiable components of the architecture or training objective. Others embed symbolic reasoning procedures—inference engines, constraint solvers—directly within neural architectures as specialized modules. Still other approaches separate concerns: neural networks handle pattern recognition and produce probability distributions, while symbolic inference operates over these distributions to enforce structural constraints and produce coherent outputs.

Each integration strategy involves distinct tradeoffs in expressiveness, computational efficiency, and ease of implementation. Some preserve end-to-end differentiability, enabling gradient-based learning throughout the system. Others sacrifice differentiability for the guarantee that symbolic constraints will be perfectly satisfied. Some require extensive domain knowledge to be encoded upfront, while others aim to learn as much as possible from data.

We defer detailed examination of these approaches to subsequent chapters, where we will explore their mathematical foundations, implementation strategies, and empirical performance. For now, it suffices to recognize that the space of possible neuro-symbolic architectures is rich and that no single approach dominates across all applications and requirements.

Looking Ahead

Each of these integration strategies represents a different point in the design space of neuro-symbolic systems, with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate use cases. In the chapters that follow, we will examine several of these approaches in depth:

-

Logic as Loss: How can logical constraints be compiled into differentiable loss functions that guide neural network training? What are the strengths and fundamental limitations of this approach?

-

Logic as Network Architecture: How can we compile logical knowledge directly into neural network structures, creating architectures that structurally enforce certain constraints?

-

Structured Prediction: How can we separate pattern recognition from constraint satisfaction, using neural networks for the former and symbolic methods for the latter? What training procedures enable this separation?

-

Learning with Reasoning: How can we train neural networks to guide or invoke symbolic reasoning procedures, particularly when these procedures are not differentiable?

Throughout, we will examine concrete applications that demonstrate both the power and the current limitations of neuro-symbolic approaches. The goal is not to declare a winner in some competition between paradigms, but to understand how to effectively combine their complementary strengths.

The challenge of building AI systems that are simultaneously data-efficient, logically consistent, interpretable, and capable of robust generalization remains open. Neuro-symbolic modeling represents not a final answer, but a promising direction—a recognition that the future of AI likely lies not in the dominance of a single paradigm, but in their thoughtful integration.

As Picasso observed, every act of creation begins with destruction. The neuro-symbolic vision requires us to move beyond the pure neural network paradigm that has dominated recent years—not by abandoning its successes, but by recognizing its limitations and augmenting it with the structured knowledge and reasoning capabilities that symbolic AI pioneered. The synthesis that emerges may give us systems that finally move beyond pattern matching toward genuine understanding.

References

- Westfall, J. E., & Sheehan, W. (2015). Celestial Shadows: Eclipses, Transits, and Occultations (Number 410). Springer.

- Wang, A., Pruksachatkun, Y., Nangia, N., Singh, A., Michael, J., Hill, F., Levy, O., & Bowman, S. (2019). SuperGLUE: A Stickier Benchmark for General-Purpose Language Understanding Systems. In H. Wallach, H. Larochelle, A. Beygelzimer, F. dAlché-Buc, E. Fox, & R. Garnett (Eds.), Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (Vol. 32). Curran Associates, Inc.

- OpenAI. (2023). GPT-4 Technical Report (Number arXiv:2303.08774). arXiv. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2303.08774

- Zellers, R., Holtzman, A., Bisk, Y., Farhadi, A., & Choi, Y. (2019). HellaSwag: Can a Machine Really Finish Your Sentence? In A. Korhonen, D. Traum, & L. Màrquez (Eds.), Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (pp. 4791–4800). Association for Computational Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.18653/v1/P19-1472

- Singhal, K., Azizi, S., Tu, T., Mahdavi, S. S., Wei, J., Chung, H. W., Scales, N., Tanwani, A., Cole-Lewis, H., Pfohl, S., Payne, P., Seneviratne, M., Gamble, P., Kelly, C., Babiker, A., Schärli, N., Chowdhery, A., Mansfield, P., Demner-Fushman, D., … Natarajan, V. (2023). Large Language Models Encode Clinical Knowledge. Nature, 620(7972), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06291-2

- Raffel, C., Shazeer, N., Roberts, A., Lee, K., Narang, S., Matena, M., Zhou, Y., Li, W., & Liu, P. J. (2020). Exploring the Limits of Transfer Learning with a Unified Text-to-Text Transformer. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 21(140), 1–67.

- Gao, L., Biderman, S., Black, S., Golding, L., Hoppe, T., Foster, C., Phang, J., He, H., Thite, A., Nabeshima, N., Presser, S., & Leahy, C. (2020). The Pile: An 800GB Dataset of Diverse Text for Language Modeling (Number arXiv:2101.00027). arXiv.

- Soldaini, L., Kinney, R., Bhagia, A., Schwenk, D., Atkinson, D., Authur, R., Bogin, B., Chandu, K., Dumas, J., Elazar, Y., Hofmann, V., Jha, A., Kumar, S., Lucy, L., Lyu, X., Lambert, N., Magnusson, I., Morrison, J., Muennighoff, N., … Lo, K. (2024). Dolma: An Open Corpus of Three Trillion Tokens for Language Model Pretraining Research. Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), 15725–15788.

- Penedo, G., Kydlíček, H., Allal, L. B., Lozhkov, A., Mitchell, M., Raffel, C., Von Werra, L., & Wolf, T. (2024). The FineWeb Datasets: Decanting the Web for the Finest Text Data at Scale. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 37, 30811–30849.

- DeepSeek-AI, Liu, A., Feng, B., Xue, B., Wang, B., Wu, B., Lu, C., Zhao, C., Deng, C., Zhang, C., Ruan, C., Dai, D., Guo, D., Yang, D., Chen, D., Ji, D., Li, E., Lin, F., Dai, F., … Pan, Z. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report (Number arXiv:2412.19437). arXiv.

References

Colby, K. M. (1972). Simulating neurotic processes. In R. C. Schank & K. M. Colby (Eds.), Computer Models of Thought and Language (pp. 491-503). W. H. Freeman.

DeepSeek-AI, et al. (2024). DeepSeek-V3 Technical Report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.19437.

Devlin, J., Chang, M. W., Lee, K., & Toutanova, K. (2019). BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of NAACL-HLT (pp. 4171-4186).

Gao, L., Biderman, S., Black, S., Golding, L., Hoppe, T., Foster, C., … & Leahy, C. (2020). The Pile: An 800GB dataset of diverse text for language modeling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00027.

Jiang, Y., Natarajan, V., Chen, X., Rohrbach, M., Batra, D., & Parikh, D. (2018). Pythia v0.1: the winning entry to the VQA Challenge 2018. arXiv preprint arXiv:1807.09956.

Kaplan, J., McCandlish, S., Henighan, T., Brown, T. B., Chess, B., Child, R., … & Amodei, D. (2020). Scaling laws for neural language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2001.08361.

McCarthy, J. (1959). Programs with common sense. In Proceedings of the Teddington Conference on the Mechanization of Thought Processes (pp. 75-91).

McCarthy, J., & Hayes, P. J. (1969). Some philosophical problems from the standpoint of artificial intelligence. In Machine Intelligence (Vol. 4, pp. 463-502).

Penedo, G., Kydlíček, H., Lozhkov, A., Dang, M., Millman, M., Etcheverry, M., … & von Werra, L. (2024). The FineWeb datasets: Decanting the web for the finest text data at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.17557.

Radford, A., Narasimhan, K., Salimans, T., & Sutskever, I. (2018). Improving language understanding by generative pre-training. OpenAI Blog.

Singhal, K., Tu, T., Gottweis, J., Sayres, R., Wulczyn, E., Hou, L., … & Natarajan, V. (2023). Towards expert-level medical question answering with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09617.

Soldaini, L., et al. (2024). Dolma: An open corpus of three trillion tokens for language model pretraining research. Proceedings of ACL 2024.

Weizenbaum, J. (1966). ELIZA—a computer program for the study of natural language communication between man and machine. Communications of the ACM, 9(1), 36-45.

Figures Required

-

Figure 3: Visual question answering example showing desk workspace image with question “Where is the penguin?” and model’s predicted answers with confidence scores (on desk: 37.025%, desk: 15.443%, on table: 12.358%, nowhere: 6.715%, floor: 4.579%). Include attention visualization highlighting the desk area. Add second panel with question “Is there a penguin in the image?” and responses (no: 100.000%, yes: 0.000%).

-

Figure 4: The word “zoological” in italicized serif font with the letter ‘c’ circled in red.

- Figure 5: Natural language inference example showing:

- Premise: “Before it moved to Chicago, aerospace manufacturer Boeing was the largest company in Seattle.”

- Hypothesis: “Boeing is a Chicago-based aerospace manufacturer.”

- Visualization showing the three-way classification (Entailment/Contradiction/Neutral) with Entailment at 75.6%

- Include book cover image of “Celestial Shadows” by Westfall & Sheehan

- Figure 6: Logical diagram showing three statements in boxes:

- P: “John is on a train to Berlin”

- H: “John is traveling to Berlin”

- Z: “John is having lunch in Berlin” With arrows showing P → H (labeled “Entails”), H → Z (labeled “Contradicts”), and dashed arrow from P to Z (labeled “No relationship?” or “Contradicts by transitivity”)

-

Figure 7: Historical photo of John McCarthy (the black and white photo from the slides)

- Figure 8: Simple illustration showing a desk at home, a car at home, and an airport in the county, representing the planning scenario

-

There are uncertainties about this so-called Eclipse of Thales, including the date, whether Thales actually made the prediction, and whether it impacted the then ongoing war between the Lydians and the Medes. But we will not let such details interfere with a good story. ↩

-

Beyond technological successes, neural networks have also led to fame, wealth, Turing awards and Nobel prizes to their pioneers and early adopters. ↩

-

Superhuman performance? What does that mean? It raises a thorny question: if the ground truth for human-level intelligence is defined by “the average human”, how could models trained on such data outperform humans? We will sidestep that discussion for now. ↩

-

The definition of a token can be complicated. For our purposes, let us think of a token as a word. A hundred billion tokens corresponds to about a million books. If you read a book a day, you will have enough to keep you busy for 2,738 years. ↩

-

RISK: The Gemini 2.0 Flash example needs verification and proper citation. Current description is based on slides but may need original source documentation or reproduction. ↩

-

RISK: The 46% violation statistic needs a proper citation. This appears to be from research on NLI consistency but requires verification and source documentation. ↩